After a long drive through rural Virginia, I found myself stepping into a place that I knew well—but which didn’t really exist. It was a fascinating juxtaposition, but (as usual) I’ve gotten way ahead of myself.

Don’t Smoke in Bed, Especially If It’s Made of Newspapers…

Spring is a perfect time for touring, and Virginia is a great place to tour. Moreover, a Mercedes-Benz SL550 provides an exciting way to move from one interesting site to another. May 28-29 found me driving a large circle around Charlottesville in search of history, scenery, and great driving roads. My path was drawn from Great Roads, Great Rides by Jennings Glen and Dan Bard. It’s a terrific guide for the broader Mid-Atlantic area, and I’ve never been disappointed by its routes.

My first stop was in Orange, Virginia, one of the oldest towns in the Piedmont region, dating back to the early 1700s. The top on my Mercedes-Benz SL550 is already stored safely, and I’ve parked in front of the 1830 Holladay House. It has a long history of notable owners, including Orange Mayor John Chapman, and it served as a bed & breakfast inn from the mid-1940s to 2021—another casualty of the pandemic. (Photo of Dr. Lewis Holladay and his wife Helen courtesy of the Orange Presbyterian Church.)

This area was originally explored in 1716 by Virginia Governor Alexander Spotswood and other prominent citizens, calling themselves the “Knights of the Golden Horseshoe.” (As best I can tell, this group invented “glamping,” as described in this entertaining issuu.com article.) Of course, Native Americans had lived here for thousands of years, but by 1700 the predominant Manahoac Indians had been driven away by rival tribes, leaving the area abandoned.

Orange was previously called “The Town of Orange County Courthouse.” The third and current courthouse was built in 1859, and it’s the only Italianate style courthouse I can remember seeing in the Mid-Atlantic region. And yes, that’s a monument to fallen Confederate soldiers on the right. Per recent news articles, the statue’s days are probably numbered.

It wasn’t until I reached the railroad station that I realized I’d been to Orange before—back in 2009 as it turned out (see A Rainy Excursion to Virginia. Trains haven’t stopped here since the early 1970s, and the building now houses the Orange County Department of Tourism. An earlier station was destroyed by a massive fire in 1908—along with the rest of the eastern half of Orange. The fire started when 77-year-old “Colonel” Towles Terrill lit his pipe and dropped the match on the floor of his tiny, cluttered apartment. (His bed consisted of a wooden box piled with old newspapers.) Towles survived, but only until 1916, when he dropped another match in his replacement apartment, causing another large fire and ending his days due to smoke inhalation.

Rapidan is a small town located a few miles from Orange. The Waddell Memorial Presbyterian Church has served as an iconic feature of Rapidan since 1874. Its distinctive “Carpenter Gothic” architecture is considered the finest example in the state. The church is named in honor of James Waddel (1739-1805), about whom we’ll learn more in a bit. (Interior photo courtesy of “JimH” in Old House Dreams.)

The Birthplace of Zachary Taylor (Maybe)

In planning my trip, I was hoping to get a look at the Hare Forest Farm outside of Orange. Getting to the general vicinity involved this narrow, rambling dirt road.

Eventually, I found the farm and its stately farmhouse—but by this time, I realized I was driving on the property’s driveway (oops). This hasty, over-the-windshield photo shows the three main sections of the old place: The 2-story main house (early 1800s), 2-story dining room addition (early 1900s), and a 1-story kitchen wing (mid-1900s). Elsewhere on the property are additional houses, barns, a smokehouse, unidentified ruins, and a stone tower for good measure. (The closer picture below and numerous additional photos of the property are available from Land and Farm.)

The property that became Hare Forest Farm was bought by William Strother in 1778 or 1779. His daughter, Sarah, married Richard Taylor, and in November 1784 the couple had a baby boy whom they named Zachary. Young Zachary went on to have a stellar military career and become the twelfth President of the United States. Many believe he was born here, at Hare Forest Farm.

However… The Strother and Taylor Families decided that Hare Forest was “farmed out” and prospects would be better in the new territory of Kentucky. So, sometime in 1784 they packed up their belongings and left for what became Louisville. After just 1 day, a member of the group became sick, and the party took refuge at the home of their kinsman (Mr.) Valentine Johnson for 6 weeks, while their comrade recuperated. Tradition suggests that Zachary was born here, at Montebello, rather than at Hare Forest. The future President himself apparently did not know where he was born, referring only to “Orange County, Virginia.” Despite 238 years of subsequent historical research, no one else knows for sure either. (The historical photo from the Library of Congress shows a view of Montebello from around the corner, where the main entrance is located. Unless otherwise cited, all historical photos are courtesy of the Library of Congress, the National Register of Historic Places, or Wikipedia.)

The Wreck at Fat Nancy

Back in July 1888, the road shown below did not exist. And the deepening swale seen at left continued on into the distance, getting deeper, before finally rising again near the house in the far distance. The Virginia Midland Railroad tracks ran along here and crossed the gully on a wooden trestle bridge, 44 feet above Laurel Run. Every day, for each train that came through, local resident Emily Jackson would happily wave to the engineer and any passengers. Her day job was washing clothes for neighboring homes, but she also kept an eye on the trains and reported anything unusual to the railroad.

This being the south in the 1880s, and Ms. Jackson being an African American, the train crews nicknamed her “Fat Nancy.” But they always waved back to her and occasionally gave her a bucket of coal in payment for her “trainspotting.” The bridge was known to be in poor condition, and the railroad’s chief civil engineer, Cornelius J. Cox, had already designed an earthen embankment and stone culvert to replace it. But at 2:00 a.m. on July 12, 1888, the trestle collapsed under a southbound passenger train moving at just 6 mph. The middle part of the train fell instantly down into the creek, dragging the locomotive and most of the other cars with it, killing 9 and injuring another 26. An article in the Alexandria Gazette closed with, “This is the first time in the history of this [rail]road that a passenger has been killed on it, notwithstanding frequent accidents have occurred, and this is decidedly the most serious one.” (Historical photo courtesy of Images of Orange County. Ms. Jackson may be one of the African American women looking on in the foreground.)

Some of the passengers were former Confederate soldiers, returning from a reunion at the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. One such was General James Longstreet, Robert E. Lee’s “Old War Horse.” He was not badly injured and worked through the night to help the injured. One of the deceased was engineer Cox; his plan would have replaced the trestle and prevented the tragedy, but it had not yet been implemented. (Photo of Longstreet at the reunion courtesy of John Banks’ Civil War Blog. He is the older man with long white whiskers. There are no known portraits of Ms. Jackson or Mr. Cox.)

Despite a broken bone in my left foot and a very dodgy right ankle, I decided to walk down to the creek. This stone culvert was built as part of Cox’s plan, with the train tracks crossing along the new embankment and over the culvert.

Hmmm. How far back did I have to walk to rejoin the SL550? It seemed much longer than the actual 414 feet that Google Maps indicates…

Mansions and Churches

The Old Blue Run Baptist Church dates back to 1769 and celebrated its 250th anniversary a couple of years ago. Both white and black parishioners were welcomed, but following the Civil War, the white congregation declined to zero. A second Blue Run Baptist Church is located less than 2 miles away, built in 1876 for the white congregants. Prior to the American Revolution, the Church of England was Virginia’s official state church—and Baptists often faced persecution. In 1788, Old Blue Run’s minister, John Leland, worked hard to convince James Madison (“Father of the American Constitution”) to add a Bill of Rights that would ensure religious freedom throughout the new United States. He succeeded.

At Old Blue Run, I was puzzled by this somewhat ungainly stone structure in the front yard. I later learned that it is the final resting place of one Jane Webb, a white woman who was thrown from her horse here in 1783. As an article in the Orange County Review states, “…enslaved people built her tomb. Those long-ago laborers may well have included the two men whom Webb herself owned.”

Next on my list was the Barboursville mansion in (naturally) Barboursville, VA. The day was extremely hot, so I picked a shady place to park.

James Barbour (1775-1842) was an American politician, serving as the 18th Governor of Virginia, a U.S. Senator, and Secretary of War under President John Quincy Adams. As a wealthy plantation owner, he could afford to build an elaborate mansion for his family in 1822, which he named Barboursville. It was based on a design by his friend Thomas Jefferson. Sadly, the mansion was destroyed by fire on Christmas Day, 1884, leaving only the walls and columns standing.

Although the place was huge, it had only 8 primary rooms—in part because the entrance hall, drawing room, and dining room were each two stories tall.

Remember James Waddel, for whom the Waddell Presbyterian Church was named? He was known as “The Blind Preacher” and was famous for captivating his congregations with moving, fervent sermons. Author William Wirt described him thusly: “In person he was tall and erect, his mien was unusually dignified, and his manners graceful and eloquent. Under his preaching, audiences were irresistibly and simultaneously moved, like the wind-shaken forest.” Previously, he had studied at the “Log College” in Pennsylvania and had later tutored such luminaries as James Madison, James Barbour, and Meriwether Lewis (of “Lewis and Clark” fame). By age 48, cataracts had destroyed his eyesight, but he remained as active as ever. This stone marks the location of the log church that he had personally built by hand.

No shade this time, just the glowing sight of a handsome sports car.

Continuing on, I drove into Gordonsville and soon located the Exchange Hotel. The town got its start in 1794 when Nathaniel Gordon established a tavern here. By the mid-1800s, Gordonsville was a bustling hub for both railroads and highways, and the Exchange Hotel was built in1860 to assist travelers. Soon, it was used as a hospital, treating as many as 23,000 wounded Confederate and Union soldiers in a single year. After the war, a Freedmen’s Bureau was established, providing educational, healthcare, and legal assistance to newly freed slaves. The hotel continued to function until the 1940s.

Today the Exchange Hotel Civil War Museum is located here—and it’s a great little museum. Indoor photos are not allowed, unfortunately, but my errant camera somehow insisted on taking this one. The docents were extremely knowledgeable and helpful, and I heartily recommend a visit here. (And I’m told that the old place is thoroughly haunted; ghost tours are given every Friday night.)

The things you find out later… On my way from Gordonsville to Keswick, I drove right by the road to actress Sissy Spacek’s farm, without realizing that she even lives in Virginia. Two little-known facts: First, one of her daughters is named “Schuyler” (pronounced “skylar”). Second, Sissy’s farm is located 30 miles from the tiny town of Schuyler, VA. Coincidence?

Everywhere I turned, there were magnificent churches and homes. After looking at the Grace Church in Cismont, VA, I decided that every church should look like this one. A small, Church of England chapel was built here in about 1750. The present stone building was completed in 1855 but suffered a devastating fire in 1895, leaving only the tower and 4 walls standing. It was soon rebuilt in its original form and continues to hold services to this day—including the annual “Thanksgiving Blessing of the Hounds Service,” prior to the town’s longstanding fox hunt. Riders, and their horses and hounds, are all part of the service, which is held outdoors for some reason…

I stopped to admire this sundial on the grounds of Grace Church. I checked its time against my watch and found that they differed modestly. Of course, “sun time” isn’t the same as “clock time.” I hadn’t corrected for location, eccentricity, or obliquity. And the sundial hadn’t corrected for daylight savings time!

As usual, I was unable to resist photographing the SL550 at every opportunity. The obelisk in the background marks the grave of James Maury, who was the first rector of the Grace Church—and also the tutor of Thomas Jefferson.

If fox hunting isn’t your cup of tea, a more sedate experience is available at Keswick Hall, a luxurious hotel and golf resort. It was built in 1912 as a family estate, later became a country club, and was reincarnated as a hotel in the 1990s. Keswick Hall reopened earlier this year, following a 2½-year renovation. As I motored up in front of the main building, uniformed staff jumped out from all directions, ready to whisk my luggage away, find me a Ginger Margarita or some Vodka Thyme Lemonade, and check me in. I had to explain that I was just a lowly tourist, taking pictures. Even so, they still offered to park the SL550 for me!

As nice as Keswick Hall would have been, I already had a reservation at another establishment—in Schuyler, VA. On my way there, I sought out Little Keswick to see what remained of the old train station. The station is said to have been built in 1849, but that was the original one—burned to the ground in 1865 by Union General Philip Sheridan and his troops. It was replaced by a larger brick station. I wasn’t exactly sure where it was, and—not for the first time—I drove right by it without noticing. I did, however, discover this modest mansion, which in 1963 became the Little Keswick School. Throughout its history, this school has helped boys aged 9 to 17 who have autism, developmental problems, or other challenges. Little Keswick School has expanded substantially and now occupies 25 acres, with the old railroad station serving as its dining hall.

After a lot of digging around, I concluded that the above mansion started life as a small, 2-room cabin in the early-to-mid 1700s. It was expanded over the years, becoming “Broad Oak” in the process. It was owned from 1861 to about 1908 by Edward C. Mead, who, in 1899, wrote Historic Homes of the South-West Mountains Virginia—and included Broad Oak among the 27 homes he described.

As a side note, another railroad station was built in 1947 when the tracks were realigned. That station also still exists, barely. The opening scenes from the movie Giant, starring James Dean, Elizabeth Taylor, and Rock Hudson, were filmed at this station, with fox hunt riders in the background courtesy of the Keswick Hunt Club. (Unbelievably, I also drove by this station without realizing its significance. I gotta plan these trips more carefully!) In the movie clips, Rock Hudson is the gent in the light-colored hat, while Elizabeth Taylor is riding the dark bay horse (side-saddle, no less). The town name on the station was temporarily changed to match the movie’s narrative.

Edward Mead wrote that he could see the South Plains Presbyterian Church from his front door. In my case, I drove the quarter mile there and got this view. It was built sometime in the 1820s and is still active.

An Old Road with Quite a History

As settlers spread across Virginia in the early 1700s, a number of crude roads were built, often following existing Indian trails. Almost all of these early roads have either disappeared or been replaced by modern roadways. In the case of “Three Notch’d Road,” however, several of its original sections still exist, largely unchanged from their original appearance. In its day, Three Notch’d Road was the primary east-west route through central Virginia. Its name stems from the three axe marks cut into trees to mark its passage. (Some parts were called “Three Chop’d Road.” Both names survive in various places between Richmond and Charlottesville.) Modern Route 250 and Interstate 64 have replaced most of the original road. This section, however, still meanders happily down toward Mechunk Creek and the presence of Major History. Only the “tar and chip” surface differs from the dirt road of 1781.

If I had been on this section of Three Notch’d Road exactly 240 years and 51 weeks earlier, I would have heard thundering hoofbeats and encountered a 6’4”, 220-pound captain in the Virginia militia named Jack Jouett as he rushed toward Charlottesville. The day before Jouett’s ride, the traitor Benedict Arnold and his English troops had attacked Richmond. The Virginia General Assembly, including Governor Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Daniel Boone, and others, had rushed to Charlottesville to avoid capture. British General Charles Cornwallis ordered 250 cavalrymen to secretly race there and capture these important politicians in just 24 hours.

By chance, Capt. Jouett had observed the British troop movements that night as they left Louisa County, and he deduced what their mission was. If he left immediately, he had a fighting chance of reaching Charlottesville before the cavalry. Racing along Three Notch’d Road, Capt. Jouett arrived at Thomas Jefferson’s home, Monticello, at about 5:00 a.m., having traveled 40 miles in just 7 hours with only moonlight to guide him. There, he warned the future President of the British plan, then charged into Charlottesville to his father’s Swan Tavern and alerted the other assemblymen. Jefferson, who had delayed his departure to relocate his family and gather his papers, rode off just as the British cavalry reached Monticello’s front lawn. Jefferson lost them in the woods and made his way to safety. The General Assembly reconvened in Staunton, VA on the other side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, although 7 members had been captured in Charlottesville (including Daniel Boone). The Assembly rewarded Capt. Jouett for his heroic actions, and he lived another 41 productive and happy years. In Virginia, he is remembered as “the Southern Paul Revere.”

As I like to say, you can stand just about anywhere in the eastern United States, and something noteworthy will have happened at that exact spot.

As further evidence of this assertion, I continued on Three Notch’d Road until reaching Mechunk Creek. I was hoping to spot the ruins of the Allegre Tavern, which had been established by French émigré Dr. James Giles Allègre in 1745. During the British invasion of Virginia, the Marquis de Lafayette and his French troops had camped here in 1781, establishing a position that prevented Cornwallis from crossing Mechunk Creek and at the same time protecting the critical war matériel needed for the coming battle at Yorktown. I had read that the old tavern still existed but was in poor condition, so imagine my surprise when I discovered it, high up on the bank and looking resplendent after a major renovation! It’s now a private residence.

Did I mention that said matériel was critically import to George Washington and the colonial troops in winning the Battle of Yorktown, which prompted Cornwallis to surrender, which effectively ended the American Revolution? Little-known places, big historical significance.

As for Mechunk Creek, after several days of rain it looked swollen and muddy. And, after all these years, still remote.

At the other end of this section of Three Notch’d Road, I found Boyd’s Tavern. The original tavern here was built in 1750 for Thomas Jefferson’s brother-in-law. Jefferson, Lafayette, and Daniel Boone all visited here. The tavern was badly damaged by fire in 1780, and a replacement went up using the original foundation and chimneys. It continued to operate as a tavern until the late 1930s.

The President’s Plane Home Is Missing

Everybody knows that Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and James Madison’s Montpelier are located near Charlottesville and are open to the public. But relatively few realize that James Monroe (5th President, 1817-1825) lived nearby as well, at “Highland” (also known for a time as “Ash Lawn”). Here is a statue of President Monroe, in the gardens of his estate.

Despite the blisteringly hot day, it was fun to roam around in the shade of these tall hedges.

Monroe built Highland in 1797-1799, calling it his “log castle” and expanding his home many times. When I reached the main house, I was surprised to learn that it was not James Monroe’s Highland! Turns out that his home burned to the ground in about 1829, 4 years after Monroe had sold it to help cover his many debts. What’s here is Highland’s 1818 guest house, with subsequent additions and modifications, including the yellow farmhouse portion added in 1873. Remarkably, this history was only sorted out in 2016.

Archeologists have located the foundations of Monroe’s original house. Other buildings on the estate are original to Monroe’s time. The smokehouse is closest to the camera, the overseer’s cabin is the farthest, and in between is a reconstructed “quarters,” typical of where enslaved African Americans would have lived on the plantation. Highland has been owned by the College of William and Mary (Monroe’s alma mater) since 1974.

Among the furnishings and possessions shown in the quarters, the period money would have been highly atypical. Enslaved people seldom had the opportunity to receive any wages for their forced labor.

Seeing the well-known Michie Tavern again brought back memories of having lunch here with my wife back in the mid-1980s. William Michie built the central portion in about 1772 as a home, in Earlysville, and began operating a tavern in 1784. It continued as a tavern until 1850 and was later sold to the state of Virginia to settle back taxes. By 1927, the building was run down and deteriorating. An enterprising woman named Josephine Henderson bought the place, had it carefully marked and disassembled, moved it 17 miles to Charlottesville, and had it put back together again as a museum. In the process, she renovated the tavern and added several other old buildings. Today it’s an extremely popular place to visit and dine—and still offers a menu nearly identical to the fare available in the late 1700s. (Photo of Michie Tavern in Earlysville courtesy of Michie Tavern.)

By now I was well south of Charlottesville, in Keene, having enjoyed Glen and Bard’s winding route immensely. The SL550 can safely and effortlessly cover many miles in remarkably little time, and it was once again proving to be the ideal touring platform. A log Church of England stood near here in 1738 and was succeeded by several more substantive buildings over the years. After the disestablishment of the Church of England following the American Revolution, there were no active churches here for 45 years. Finally, in 1832, the Episcopalian Christ Church at Glendower was constructed. It cost $1,788 and is believed to have been built by William Phillips, a talented brick mason who had helped Thomas Jefferson build the University of Virginia. It’s been in continuous use ever since.

Nearby, a parsonage was built in 1848 and has been called “The Rectory” ever since. It’s a nice-looking colonial house in Greek Revival style, but it sits on an odd stone and brick foundation. The older brick portion is believed to have supported Dyer’s Store from 1787 to about 1810, which provided goods, food, and drink for local residents, and accommodations for travelers. Samuel Dyer had emigrated from England in 1770 and fought for independence on the American side in the Revolutionary War.

Speaking of churches… In Scottsville I found the most unusual Baptist Church I’ve ever seen. The Union Baptist Church was formed in 1865, immediately after the Civil War, and its African American membership originally worshipped under a tall oak tree. Later, as resources permitted, they built a modest, wood-frame church building. By the early 1950s, however, it was in poor condition, and Rev. Houston Parry designed the current edifice. With the help of parishioners, Rev. Parry built the new church using cinderblocks for protection against fire. It’s still going strong. (Photo of the first service courtesy of the Scottsville Museum.)

A Burial in a Ghost Town

In its day, the town of Esmont was a thriving stop on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. It had numerous houses, 3 stores, a school, the railroad station, and its own bank. This 1910 photo shows Steed’s Store in the foreground, the Esmont Inn next to it, the Esmont National Bank further away, and the C&O Railroad Station in the distance. (Photo courtesy of Friends of Esmont.)

Today, Esmont is well on its way to becoming a ghost town. This is the Purvis Store; once the most popular spot in town, it’s now teetering on the verge of collapse. There are plans to restore the old place, but it would be quite an undertaking.

Pace’s Store and Service Station could also use a helping hand.

Steed’s Store is in a similar situation but is still easily recognizable. It closed in 1963. The station and tracks are long gone, as is the Esmont Inn, but the bank building survives and now serves as the post office.

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church is still doing well, despite a declining number of members. In the third photo, the fellow with the shovel is lamentably on his way to dig a new grave in the cemetery.

An Overnight Stay in a Place that Never Existed

After Esmont, it was a short hop to my overnight destination in Schulyer. Although I’d never been here before, the exterior of the bed & breakfast looked quite familiar, as did the Ford Model A coupe parked outside.

The contrast between my Mercedes and the Model A was rather pronounced (although perhaps not quite as much as between my Aston Martin Vantage V8 and a Ford Model T, as shown in Aston Martin vs. Ford Model T on the Lincoln Highway).

As mentioned in my opening sentence, one step through the door and I immediately recognized where I was—although my familiarity was of a place that doesn’t actually exist. And the more I looked around, the greater the familiarity became!

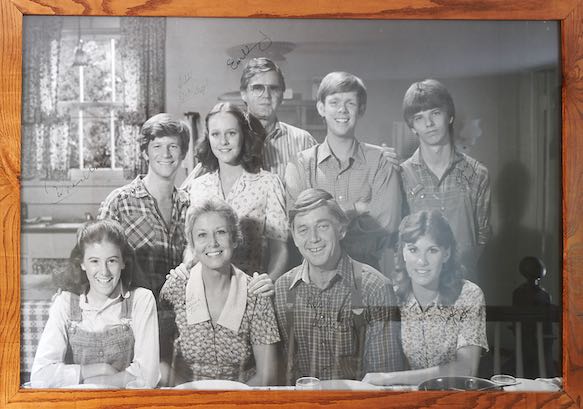

As many of you have figured out by now, I was in a recreation of the family home from The Waltons TV show (1972-1981). Owner and proprietor Carole Johnson is undoubtedly the most knowledgeable and passionate Waltons fan in the country. And she has created “John & Olivia’s Bed & Breakfast” for the benefit of Waltons fans throughout the world. When the doors opened in November 2019, her first guests were original cast members Eric Scott (Ben), Kami Cotler (Elizabeth), Mary Beth McDonough (Erin), Judy Norton (Mary Ellen), and Jon Walmsley (Jason).

So why did Carole do this in Schuyler, Virginia? Well, that’s where Earl Hamner, Jr. grew up and first wrote about his family, which became the model for The Waltons. The characters are all based on Hamner’s parents and siblings, and he both scripted and narrated the TV show. As for Carole, she started collecting Waltons’ memorabilia decades ago, and when the 1915 Hamner House went up for sale in 2017, she was the one to buy it. It’s also available for tours and as a place to stay.

Thanks, Carole, for your outstanding hospitality and the thorough tours of both the B&B and the Hamner House. I thoroughly enjoyed it all (and breakfast was delicious, especially the blueberry scones!)

Did I mention that Sissy Spacek appeared in 2 episodes of the Waltons? Or that a grown-up Kami Cotler moved to Norman County, VA and taught in a small rural school near Schuyler?

Soapstone

At one time, Schuyler was a sizable industrial town with an area population of more than 7,000. The prosperity of both Schuyler and Esmont was due to the quarrying and finishing of soapstone. “Alberene” soapstone was first mined here by James Serene in 1884, with its name combining parts of Albemarle County and Serene. This type of hard soapstone is found in small quantities elsewhere around the world, but it was only ever successfully mined in Schuyler/Esmont. It has been used for sinks, bathtubs, tile, countertops, sculpture, and even stoves and fireplaces. The Alberene Soapstone Company thrived for many years, building housing for its 1,300 workers and their families, a school, hospital, movie theatre, and (naturally) the company store. Eventually most of the soapstone fields became empty quarries, and the company largely closed its doors in 1973. (Historical photo of an ASC worker courtesy of the Slippery Rock Gazette. Honest!)

One place I missed but really wish I’d known about was the Alberene Soapstone Company House. (It’s on my list for the next time I’m in that area.) Shown below is Kipp Teague’s excellent photo on flickr. If you look closely, you’ll see that the first story of the house is made of soapstone.

Native Americans mined soapstone here as far back as 3000 BC/BCE. They used the stone to make bowls and utensils, which were traded among tribes all across eastern North America. The Quarry Gardens at Schuyler showcase 2 of the original quarries.

This dam on the Rockfish River supplied power for the mining operations and for the company houses where the workers lived. The generating equipment was destroyed in a 1969 flood, but work is now underway to revitalize the site. With the enthusiasm for stone countertops in the 21st century, the Alberene Soapstone Company reopened in 2004 after years of desultory operation. Its 25 workers represented only a small fraction of the number that used to quarry and finish the slabs, but it was still a promising sign. As best I can tell, however, the company has once again ceased operations. (Photos of Rockfish Dam at Schuyler before and after Hurricane Camille courtesy of the Library of Virginia.)

Those Charming Langhorne Ladies

The Schuyler Baptist Church was built in 1907 and served the Hamner Family and many others. In 1940, Earl Hamner, Jr. was awarded a scholarship to the University of Richmond (the model for “Boatwright University” in The Waltons). A condition, however, was that Hamner had to know Latin. In addition to his summer jobs that year, he spent the summer busily learning Latin from the church’s pastor.

On a hill just outside of Schuyler, I “discovered” this Gothic Revival church, beautifully covered by ivy. It was originally the Christ Episcopal Church from 1920, but over time the congregation dwindled, and the church finally closed. During the flood of 1969, a group of Mennonites were instrumental in helping to save area residents. When the Alberene Soapstone Company reopened, the new owners purchased the old church and gave it to the Mennonites for as long as their church remained active. The Rehobeth Mennonite Church is still going strong.

Yeah, the car’s expression seems to say, “C’mon, let’s get going!” Leaving Schuyler on Rockfish River Road was a real treat, with constant elevation changes, a nearly continuous series of corners, and not that much traffic. Great sports car country.

The town of Rockfish does exist, and here is its post office to prove it!

Every stream or river I came to was extra full of muddy water, including the Rockfish.

We’re all used to thinking of West Virginia as an impossibly “vertical” place, but huge swaths of Virginia can also make that claim.

The bridge looks a lot more rickety than it is. I think…

Jennings Glenn and Dan Bard, having motorcycled all over the Mid-Atlantic and beyond, sure know how to pick fun routes.

Moreover, there were sights like these around every corner.

Not all of Virginia’s stately mansions were built prior to the Civil War. “Ramsay” was built by William H. Langhorne and finished in 1900. His cousin, Chiswell Dabney Langhorne, acquired Ramsay in 1914. Chilly’s grandson, Langhorne Gibson hired noted architect Milton Grigg to incorporate substantial remodeling in 1937, 1947, and the early 1950s. Daughter Irene Langhorne Gibson lived out her retirement years here. (There will be a test at the end of this report.) The estate is now a working farm, vineyard, and bed & breakfast.

Emanuel Episcopal Church is just a quarter mile down Route 250 from Ramsay. It started as a one-room building in 1863, and in 1911 it was significantly enlarged by the children of Chiswell Langhorne.

The Langhornes were an interesting family. Chiswell lost the family’s mill as a result of the Civil War but became a tobacco auctioneer afterwards. He was quite successful—and is said to have invented the rapid-fire “auctioneer’s patter.” He next became involved in railroad construction, eventually earning a fortune.

His daughter Irene Langhorne Gibson had received 62 marriage proposals by the time she was 22. Despite her father’s misgivings about her marrying an artist, she accepted Charles Dana Gibson’s proposal. Even before their marriage, Irene became the first model for the “Gibson Girl,” Charles’ iconic illustrations of the epitome of feminine beauty, culture, intelligence, and personality. Her 4 sisters were also modeling for Charles before long. Gibson Girls usually had an air of independence and were often portrayed as eminently superior to men. Irene went on to become a noted philanthropist and social activist.

And then there was daughter Nancy Langhorne, who became Lady Astor and the first female member of the British Parliament (in 1919). She served in Parliament for 25 years and was famously witty and sharp-tongued. Her exchanges with Winston Churchill are legendary. My favorite:

Lady Astor: “Winston, if I were your wife, I’d put poison in your coffee.”

Winston Churchill: “Nancy, if I were your husband, I’d drink it.”

Nancy Langhorne Astor was also controversial for other reasons, notably her anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic views, which she did not try to hide. But she worked hard promoting women’s rights and charitable organizations. In all, as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in her newspaper column in 1945, “All of the Langhorne sisters are people one has to notice!”

Taverns and a School, Then and Now

Throughout my trip, I relished the beautiful scenery.

I had stopped at this point in the hopes of getting a look at Mirador, the family home of Chiswell and Nancy “Nanaire” Langhorne and their 8 (surviving) children. It was well hidden, but I managed this distant photo. (The closer image is courtesy of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.) Mirador was built in 1842 and extensively remodeled in the 1920s by New York architect William Adams Delano.

I was also looking for Sam Black’s Tavern. No, I wasn’t particularly thirsty—I just wanted to see the historic 1769 log building that had served travelers for many decades along Route 250. It took a lot of searching, but it finally showed up on the distant grounds of Mirador, having been moved here in 2001 from a neighboring farm. The tavern’s 2 rooms are divided by a massive, off-center stone fireplace, and it is essentially unchanged from its heyday.

While looking for the tavern, I stumbled across what was clearly the most popular place in central Virginia on this day: Septenary, the Winery at Seven Oaks Farm. There were easily a couple of hundred folks there, sampling all sorts of wine and having a great time. I asked one of the hostesses if it was a special occasion, and she said, “No, just a regular weekend.” (I thought their sparkling chardonnay was great, by the way…)

In Brownsville, I took made a detour to see if I could find the Miller School of Albemarle. Today it’s a well-regarded preparatory school, but it started life in 1878 as the Miller School of Manual Labor, a charitable institution for orphaned and other disadvantaged students. Samuel Miller was born into poverty near here, but he worked his way up to become a successful businessman. At his death, he left about $1.1 million for the creation and operation of the school. “Old Main” was the first to be completed: an extraordinary building in an exceptional setting.

Up close, it’s even more impressive. Built in the “High Victorian Gothic” style, this portion of the school originally housed a cafeteria, chapel, classrooms, and rooms for the boarding students. The school taught both boys and girls, making it one of the oldest coeducational boarding schools in the U.S. White boys and girls, anyway; African American students were not admitted until 1967, to comply with the Civil Rights Act. The school was tuition-free until 1950, when Mr. Miller’s legacy could no longer provide for full educational costs.

Industrial work was taught in the Mechanical Arts Building, which was completed in 1882 with forges, metal and woodworking shops, and other hands-on classrooms. Based on historical photos, the boys learned mechanical skills, while the girls focused on sewing. In addition to these lessons, however, there were courses in “English, German, Latin, mathematics, physics, mechanics, chemistry, and biology.” In 1927, lack of funding forced a cutback to a boys-only enrollment; female students finally returned in 1990.

Nobody seemed to mind my looking around and taking pictures. Nonetheless, I tried to be discreet!

Navigating by Stone

Back on the road, I went looking for my final site of the tour.

Every so often, a glorious reminder of the industrial revolution would appear, including this old steam engine. It’s clearly a “portable engine,” which could be hauled by horses to a place where it would drive a thresher, saw, or other piece of farm equipment. Note that the tall smokestack could be folded down onto the yoke at the rear for transport. While you’re at it, note the centrifugal speed governor (the uppermost part in red). After a fun 30 minutes of looking around the Internet, I learned that this is a Frick “Eclipse” portable steam engine from roughly the 1880s.

Not everything from the 1800s is equally well preserved. Here it looks like someone was replacing the original chimney with one made of cinderblocks, but then it all went wrong…

As I was approaching my last historical site of the trip—the “Octonia Stone”—I suddenly realized that the road I was on was really someone’s driveway… And I wasn’t even sure that this was how to find the stone, since its location wasn’t clear. Thankfully, when I reached the farmhouse, a nice young fellow came over and told me exactly where the stone was. He and his brother even mow the grass around it so that tourists don’t have to wade through a thicket.

And this is the Octonia Stone. It was “built” millions of years ago and is a large granite outcropping. Remember Governor Spotswood and the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe? When they weren’t drinking and carrying on, they surveyed much of what later became the Octonia Grant, a gift from British King George I to Gov. Spotswood in 1722. The Governor, in turn, divided up the grant to eight individuals, most of whom were part of the “Knights.” The stone marks the northwest corner of the Octonia Grant, which measured about 20 miles long and 2 miles in width. Underneath all the lichen, the number 8 is engraved on the stone, with a cross on its top. The Octavia Stone was used as a landmark for surveys, deeds, and other purposes for many years.

Is there any part of Virginia that isn’t scenically beautiful?

With a last look at the Octonia Stone, it was time to dash the 137 miles through Virginia and Maryland, back to my home.

Thanks to Glenn and Bard’s excellent route, my 2-day tour was a feast of fun roads, interesting historical places, and great scenery. The SL550 got a lot of fast-paced exercise, and it impresses me more and more, every time I drive it.

Rick F.

Loved the entire article – makes me want to study US history again – especially history of the Civil War.

Had forgotten Lady Astor spoke her charming and humorous words to Winston Churchill.

Your car is indeed magnificent! Thank you so much for all the research you did.

Blessings,

Vicky Garrett

Hi Vicky!

There are a lot of fun exchanges between Lady Astor and Winston Churchill, although they aren’t all necessarily true. Another of my favorites was when Churchill was going to go to a costume party and asked her what he should go as. Lady Astor reportedly said, “Why don’t you go sober?” She was a notorious teetotaler and supporter of prohibition.

I hope you’re doing well and your concert plans are falling into place!

xoxoxo

Rick

“Despite a broken bone in my left foot and a very dodgy right ankle” Heal well my friend! What did you do to yourself?

Your SL is a wonderful steed! I truly enjoyed reading this travel episode. How many horses would it take to draw the portable steam engine? It looks massive! It’s a not-so-portable engine!

I cherish old structures that have lasted through time. I appreciate you telling their history and the names of the wonderful people that were in their lives.

And I truly appreciate you mentioning the sources you use to plan your trips. I wish I had those resources to plan travels here from my home base. I feel spoiled…a white ’22 Rubicon has joined our family.

Stay well! I’m so pleased to see this story.

DaveL

Missausaga near YYZ

Hi Dave!

Always good to hear from you. And I see that you’re continuing your rampage as a Serial Car Purchaser! I hope the new Jeep works well for you. It should be able to go anywhere in any conditions and climb just about anything (including large trees).

As for my foot and ankle, mostly what I did to myself was to just grow old! In fairness, my ankle problem also reflects old basketball injuries. With luck, my upcoming ankle surgery will restore my ability to walk long distances, in which case I’ll be back to finding even more off-the-beaten-path places.

As for the horse-drawn portable steam engine: Based on how spindly the wheels are, I’m guessing that it doesn’t weigh as much as it looks. I found a few pictures of Eclipse steam engines with towing bars attached, and they were the right length for two horses. Also, the power take-off wheels look to be a little over 6 feet from top to ground, so the engine isn’t huge.

All the best,

Rick

Rick, this is an amazing one and so enjoyed. My family has been going to our Lake Anna house for 40 years and occasionally venture into this area but never could have imagined the depth of history and places you have documented. Can’t wait to visit some of the notables in your travel log. Thanks so much for enriching our knowledge, these are amazing. Clif Gaus

Hi Clif,

Longtime no see! I hope you’re doing well, and I’m glad you enjoyed the trip report. Virginia is packed wall to wall with fascinating history and scenic beauty. I very much enjoyed my loop around Charlottesville, much of which was well off the beaten path.

Rick

Thanks Rick, as always great pictures and writing. I appreciate you taking the time to share with us all.

Hi Shannon!

You’re welcome, as always. I’m pleased that you enjoy the trip reports.

Next up will be a report on touring Connecticut, back in June. All I have to do is find the photos…

Rick