Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman is best known for his brilliant military strategies and his infamous “March to the Sea” during the Civil War. He also coined the phrase “War is Hell”—and he certainly knew what he was talking about. In a recent visit to the Fredericksburg, Virginia battlefields, I found all too much evidence supporting this view.

Over the years, from age 7 on, I’d been to Gettysburg and Antietam many times. But somehow, I’d never visited Fredericksburg. Accordingly, on January 22 I fired up the 2020 Mercedes-Benz SL550 and headed for Virginia—exactly 160 years and 40 days after the climactic First Battle of Fredericksburg was fought. The SL550 was thrilled to be back in touring action, and however much throttle I requested, it provided double that amount.

On November 5, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln removed Union Gen. George B. McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac for his failure to pursue Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army after the Battle of Antietam. (Lincoln waited until the day after the mid-term Congressional elections, since McClellan was very popular in the north. Politics was omnipresent, even back then.) Lincoln appointed Gen. Ambrose Burnside as the new lead of the Army of the Potomac—and urged him to waste no time in attacking the Confederates.

The Union Army had occupied Fredericksburg during the spring and summer of 1862. During this time roughly 10,000 enslaved African Americans in northern Virginia had escaped from bondage, traveled to Fredericksburg, and gained their freedom under the protection of the Union soldiers. It was the largest exodus of enslaved Americans in history.

Gen. Burnside, anxious to act against the Confederates, devised a plan dependent on speed and subterfuge. He appeared to move his army southwest of Washington, toward Confederate Gen. James Longstreet’s forces near Culpeper, VA—but his real goal was to drive toward the Confederate capital of Richmond as rapidly as possible, capture the city before Lee could react, and thereby end the war altogether. His plan depended critically on reaching Fredericksburg—halfway between Washington and Richmond—and crossing the Rappahannock River there. If successful, the Army of the Potomac would gain access to the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad plus two good roads to the capital, virtually unopposed. Burnside left Washington on November 15 with 120,000 soldiers. Lee’s forces were farther to the west, with Longstreet’s 40,000 near Culpeper, and Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s 38,000 in the Shenandoah Valley. Burnside’s plan was ambitious but doable.

East of Fredericksburg

To see these places for myself involved driving the SL550 down the dread I-95 through Maryland, around Washington, and into Virginia. There was a lot of traffic, but it was moving steadily, and I soon arrived in Falmouth, on the eastern bank of the Rappahannock opposite Fredericksburg. It’s not uncommon in rural Virginia to see historic buildings, such as the 1819 Union Church. Highlighted by a stunning morning sky, it was quite a sight.

Finding just one-fifth of a historic old church was definitely out of the ordinary. A torrential rainfall in 1950 left only the narthex of the church standing, complete with its 1867 bell. Union Church served four different denominations. African Americans were welcome to attend services—but had to enter by the left doorway and sit in the balcony. White parishioners would enter through the right door. During the Civil War, Union troops used the church as a barracks and, later, a hospital. The original 300-pound bell was removed and melted for ammunition. The original wooden box pews were stripped out and used as firewood.

In his youth, George Washington lived near Fredericksburg and is believed to have been initially taught by a Master Hobby, who was a sexton at Union Church. This 1880s log and brick schoolhouse is adjacent to the church and illustrates the type of building where Master Hobby would have taught classes.

Continuing on in Falmouth, I was looking for the Barnes House and expecting to find the ruins of the 1780 building that was once used as a school for African American children. To my pleasant surprise, the house has been fully renovated by new owners Jay and Katie Holloway. (Earlier photo of the Barnes House courtesy of Glass House.)

Falmouth seemed to have more historic buildings per square acre than almost anywhere. This one was built in 1807 and is named for Moncure Conway—considered to be the most outspoken abolitionist in the south. Moncure lived here from age 6 until he left to attend Dickenson College in Pennsylvania. After graduating at age 17, he became a minister and writer, preaching fiery anti-slavery sermons at the Union Church. He had to flee Falmouth in 1854 to avoid being tarred and feathered for his unpopular views. Moncure also became estranged from his family: his father was a prominent slave owner in Virginia, and two of his brothers joined the Confederate Army. Relations were probably not helped in 1862 when Moncure transported about 30 of his parents’ enslaved African Americans by train from Virginia to Ohio, where they gained their freedom. He spent most of the rest of his life in England, Italy, and France. After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Conway House served as a hospital, with poet Walt Whitman working here as an army nurse. In fact, virtually every building I saw on this tour had been used as a hospital following the battle.

In contrast to the Conway House, Shelton Cottage is more representative of a working family’s home in the late 1700s.

And this quaint-looking place probably falls somewhere in between.

Chatham Manor—and a Pair of Dedicated Public Servants

From Falmouth, I motored on until reaching the “Lacy House,” also known as “Chatham Manor.” The mansion sits high above the city of Fredericksburg on Stafford Heights. Gen. Burnside made his headquarters nearby when he and the Army of the Potomac arrived on November 17. Chatham is the only house in the U.S. visited by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln.

Chatham Manor is owned by the National Park Service and is open to the public. Chatham was built in 1769-1771 for William Fitzhugh, who owned many thousands of acres in Virginia—and well over 100 enslaved African Americans. Fitzhugh sold the plantation soon after a slave uprising here in 1805. The portrait above the fireplace is of J. Horace Lacy, who bought the mansion—and 93 slaves— in 1857 after owner Hannah Jones Coalter passed away. Her will had specified freedom for the slaves, but relatives (including her much-younger sister Betty, a.k.a. Mrs. J. Horace Lacy) sued to maintain ownership, and the Supreme Court of Virginia decided in the Lacys’ favor.

The painting here is of Betty Lacy as a child. The furniture in this room belonged to the Lacy family, including these wingback chairs. One of them features a circular hole under the upholstery, indicating that it had been used as a “chamber chair” (i.e., paired with a “chamber pot” underneath). The National Park Service staff are knowledgeable, serious, and expert researchers—and they are not without a sense of humor: A nearby sign states, “According to family tradition, George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, James Madison, James Monroe, Washington Irving, and Robert E. Lee all used this chair.” (Goodness!)

This ancient Catalpa tree is one of two at Chatham that witnessed the Battle of Fredericksburg. Both are still alive, despite their twisted, gnarled appearance, but they may not be for long. The NPS advises to visit them sooner, rather than later.

As I concluded my tour of Chatham, I bombarded NPS Ranger Hilary Grabowska with question after question about the manor’s history, details of the battle, and related topics. She enthusiastically answered every one, in the process displaying an encyclopedic knowledge of Civil War history. Thank you, Hilary, for your time and assistance, which were a highlight of my trip.

This would also be a good time to mention John Hennessy, who recently retired after a 40-year career with the National Park Service. John’s numerous articles about Fredericksburg are informative, insightful, thoughtful, and often quite poignant. His writings are available at Fredericksburg Remembered and Mysteries & Conundrums, and they merit the attention of anyone interested in the Civil War. John and Hilary serve as shining examples of dedicated public servants.

Back outside of Chatham, I took a moment to admire Pan’s gazebo and the long shadows from the adjacent tree.

When the Lacys returned to Chatham after the Civil War, they found that all the windows had been broken, the interior paneling and much of the furniture had been burned for firewood, and there were 130 graves of Union soldiers surrounding the house. With the abolition of slavery, such plantations were no longer economically viable, and they soon sold the estate.

Chatham remained in poor condition until it was purchased in 1920 and renovated. In 1975, it was bequeathed to the National Park Service and has since been used as their area headquarters. In this current view, note that the stately porticos surrounding the entrance have been removed. The bodies of the fallen soldiers were disinterred and reburied in the new Fredericksburg National Cemetery in the late 1800s.

This view of Fredericksburg from Chatham has not changed all that much since the Civil War. It’s the same view that the Union Army had when it arrayed at least 150 cannon along Stafford Heights.

A Plan Gone Awry

If Gen. Burnside’s goal was to arrive at Fredericksburg and cross the Rappahannock as quickly as possible before the Confederates could react, then why did he bother setting up such a massive artillery position? Especially given that Fredericksburg was defended by only about 500 Confederate soldiers? Well, he was expecting to receive hundreds of pontoon boats when he arrived, to be used to build new, temporary bridges across the river. (The original bridges had been burned by the Confederates earlier in the year, when Union forces were arriving to occupy the city. Union engineers then rebuilt them, but, when the Federal forces pulled out, they burned their own bridges.)

As it happened, the pontoon boats were delayed by bureaucratic snafus and bad weather. Senior officers urged Burnside to have the army ford the Rappahannock, capture the city, and establish a defensive position on the nearby hills behind the city while the main army moved on Richmond. However, Burnside was uncomfortable with that tactic and insisted on waiting for the boats. In the meantime, Gen. Lee’s scouts had observed the Union troop movements to Fredericksburg, and Lee quickly ordered both Longstreet’s and Jackson’s armies to the city.

Almost 3 weeks after Burnside’s requisition, the first set of boats arrived, enough for a single bridge. Again, Burnside’s generals urged him to cross over and attack the Confederates before Longstreet’s men had dug in and before Jackson could arrive. Again, Burnside waited for more boats. By the time the rest of the boats had arrived, Lee’s full army was in position on the western hills, and Longstreet’s men and artillery were well entrenched. Lee even had time to have a rudimentary road built along the top of the ridge, connecting all of his forces and enabling rapid repositioning of the troops if need be. Burnside’s delays set the stage for one of the costliest Union defeats of the Civil War.

The Union army still had strength in numbers (120,000 men versus Lee’s 78,000) and also certain technological advantages. This device is a portable Beardslee Telegraph unit that operates by magneto, thereby eliminating the need for large batteries. It also used an alphabet wheel, rather than normal Morse code key, and thus could be operated by anyone. (Anyone who could read and write, at least.) Unfortunately, its operation was slow and was dependent on careful coordination between sending and receiving units. Still, it gave the Union army a distinct advantage in communications during the battle.

Another innovation used at Fredericksburg was balloon reconnaissance. Helium-filled balloons were sent up at Chatham and elsewhere along Stafford Heights to monitor Confederate troop movements and direct artillery fire. The intrepid observers could also relay their findings from 1,000 or more feet in the air via the Beardslee Telegraph.

An Ominous Change in American Warfare

From Chatham, I followed the original driveway down to the river and across into Fredericksburg. The view would have been quite similar, even 160 years ago.

Finally, on December 11, 1862, Burnside had all his materials, and the Union engineers began building the pontoon bridges, six in all. They found, to their dismay, that Lee had sent a brigade of sharpshooters into the basements of the houses lining the Rappahannock. The Confederates had a direct line of fire, with dire consequences for the engineers and their teams.

In response, Burnside ordered the Union artillery to shell these houses, which were only a quarter mile away. Although the shelling promptly destroyed most of the buildings, it had little impact on the sharpshooters. Once the bridge-building recommenced, so did the shooting. In frustration, Burnside ordered the artillery to shell the entire city. As John Hennessy wrote in December 2010, “It was the first wanton, sanctioned, wholesale destruction inflicted on an American town by an American army.” Moreover, “It was a betrayal of the conservative principles of war that had so governed the high command of the Army of the Potomac since the beginning.” Up to this point, the guiding principle had been to defeat the Confederate Army but to also respect the non-combatants in the south and their property, in the hopes of reuniting peacefully with them at war’s end.

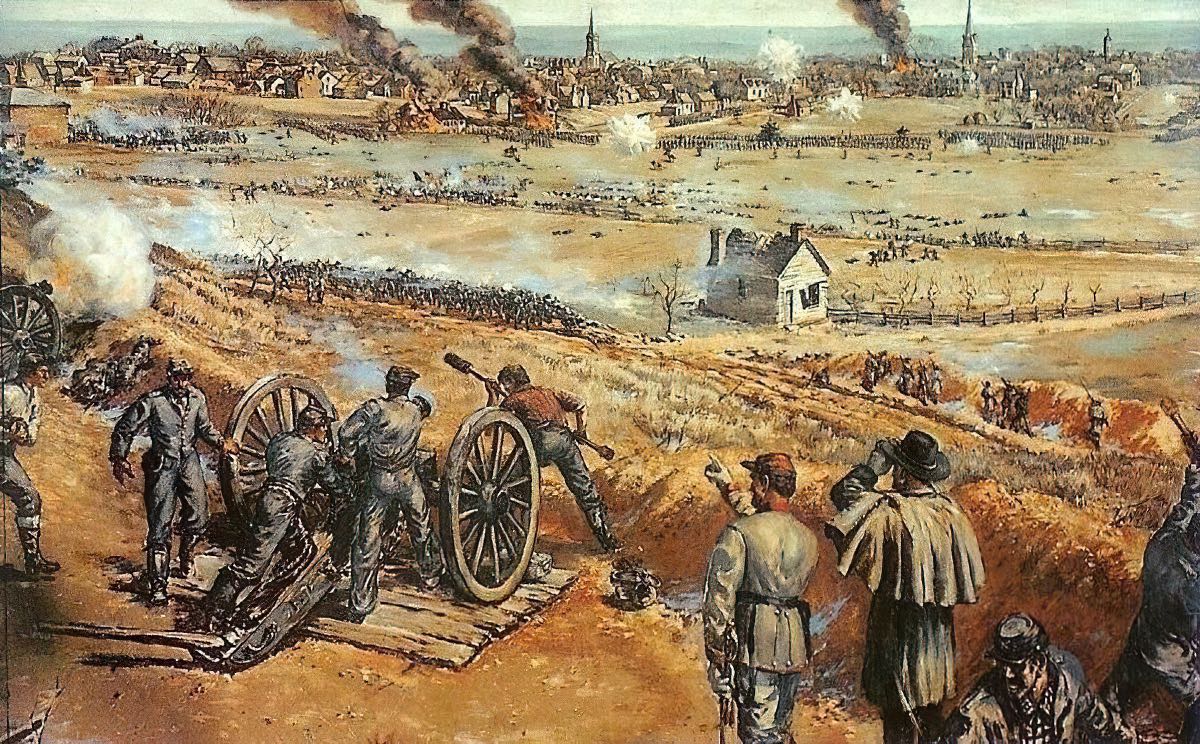

Burnside’s general in charge of the artillery, Gen. Henry Hunt, was shocked by the order and tried to talk the commander out of it. He failed, and somewhere between 150 and 180 cannons bombarded Fredericksburg relentlessly. Watching the cannonade, Gen. Lee said of the Union forces, “These people delight to destroy the weak and those who can make no defense; it just suits them.” Burnside’s decision opened the door to an ever-increasing, vengeful, back-and-forth destruction of American cities through the remainder of the war: Petersburg, Charleston, Vicksburg, Chambersburg, Atlanta, and more. (Engraving of the bombardment of Fredericksburg courtesy of Megan Kate Nelson’s excellent article Urban Destruction during the Civil War.)

Only 3 buildings closest to the river managed to survive the shelling, including this one. The Eubank House can be seen in the historical photo below, just above the second bridge pier from left.

Numerous early photographs document the damage done by the bombardment of Fredericksburg.

This photo shows two duplex houses on Caroline Street that survived the shelling. The historical photo shows the first of these duplexes after the bombardment.

As much of Fredericksburg became engulfed in fire and smoke during the shelling, the Union cannons were often trained blindly at the center of the city or at the church spires that towered above the smoke. The Fredericksburg Baptist Church survived despite substantial damage.

Likewise, St. George’s Episcopalian Church and the Fredericksburg Presbyterian Church continue to stand. Note the cannonballs still embedded in a column of the latter. All three of these churches were severely damaged; all three were also used as hospitals after the battle, with, among many others, a young Clara Barton nursing the wounded. Nineteen years later, she founded the American Red Cross.

The Shiloh Baptist Church had been an institution in Fredericksburg since its founding in 1808. Prior to 1854, its congregation comprised about 250 white parishioners and 500 free and enslaved African Americans (who entered through a side door leading directly to the balconies). A new Baptist Church was built in 1855 for the white members, with the older building becoming the “African Baptist Church.” The black membership grew quickly to over 800, but in the summer of 1862, roughly half of these individuals crossed the Rappahannock to their freedom under the protection of the Union Army.

Located near the river, the Shiloh Baptist Church was one of the most severely damaged, both from the shelling and subsequent actions of the Union troops in Fredericksburg. The upstairs was used as a hospital, while the downstairs became a military stable. Services could not resume until after the war ended and extensive repairs were made. Then, in 1886, the back wall collapsed, and the building was destroyed. It was replaced with the current church in 1890. Today, the Shiloh Baptist Church thrives, offering two services every Sunday, with six different choirs singing joyously at each one.

More Ominous Innovations: Urban Warfare and Retribution

While the bombardment of Fredericksburg was occurring, Gen. Hunt recommended to Gen. Burnside that a rapid attack be made by boat across the Rappahannock, with the intention of landing enough soldiers to overwhelm the remaining Confederate sharpshooters. This plan worked, the bridges were quickly completed, and the Union forces began to flood into the city. Street-by-street fighting ensued, with the Federal forces largely capturing the city by nightfall. (Painting of “Fire on Caroline Street” by artist and historian Don Troiani.)

Here is a view of the main crossing area at the Rappahannock today, from the Fredericksburg side with Chatham Manor in the background. The tranquil appearance belies the ferocity of the fighting that occurred here. (Henry Lovie’s illustration of the Union Army crossing into Fredericksburg is from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, December 27, 1862.)

As much as the bombardment had shocked the citizenry of Fredericksburg (and both Union and Confederate officers), what happened next was even worse. As the Union soldiers poured into town, frustrated with the long delays and feeling angry at the stiff Confederate resistance, they began to thoroughly loot the town and steal or destroy every element of its belongings. Per John Hennessy, “Of all the things that lay the groundwork for the looting of Fredericksburg those ugly days, the general nature of the bombardment was by far the most important. The general destruction inflicted by the bombardment implied, to the soldiers, sanction for the destruction to continue.” This sketch by Civil War reporter Alfred Waud illustrates the scene.

Arthur Lumley was another prolific illustrator during the Civil War. This sketch portrays the looting and destruction in Fredericksburg. As John Hennessy noted, Lumley wrote on the back of his sketch, “Friday Night in Fredericksburg. This night the city was in the wildest confusion sacked by the union troops =houses burned down furniture scattered in the streets =men pillaging in all directions – a fit scene for the French revolution and a discrace to the Union Arms – This is my view of what I saw.” (Original spelling and punctuation.)

Another vivid image of the looting was shown in Frank Leslie’s Famous Leaders and Battle Scenes of the Civil War, 1896.

The oldest exhibit in the Fredericksburg National Battlefield Visitor Center is this extraordinary diorama of the ruined city. Its level of detail is remarkable—right down to the addresses on the scattered envelopes.

The Battle Begins (Badly)

As the Federal troops continued to pour into Fredericksburg on December 12, Burnside and his generals fine-tuned their battle plans. Burnside described a massive attack by nearly the full force of General William B. Franklin’s 40,000 men against Prospect Hill, where Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate troops were still rapidly digging in for just such a move. The goal was to turn the Confederates’ right flank and drive them north along the ridge. Meanwhile, the forces of Generals Sumner and Hooker would attack Longstreet’s position at Marye’s Heights behind Fredericksburg and prevent them from retreating. With the north’s numerical advantage, the plan might conceivably have worked, but in practice it was poorly conceived and disastrously implemented.

Construction of the pontoon bridges south of Fredericksburg had gone smoothly, with little resistance. Franklin’s forces could have crossed a full day earlier—and before Jackson’s men had dug in—but Burnside delayed, waiting until the bridges at Fredericksburg were also ready. Per the National Park Service, “Had most of [Franklin’s] army marched to the right bank that night, Burnside might have been able to launch an attack early the next morning that would have caught Lee with as few as eighteen regiments protecting his right flank at Hamilton’s Crossing, instead of the eighteen brigades poised there when he finally did attack.” (Emphasis added. Each brigade would usually comprise two to five regiments.)

Moreover, Burnside failed to send the written attack orders on the night of December 12, waiting instead until the following morning. Gen. Franklin had wanted to position his troops overnight for a pre-dawn, morning attack. And then, when the orders finally arrived, they were ambiguous and not consistent with the previous day’s planning. Instead of a full attack by the six available divisions, the order read, “You will send out at once a division at least … taking care to keep it well supported and its line of retreat open.”

Gen. Franklin did not seek clarification of the orders. Gen. George G. Meade’s division of 4,500 men was selected and sent forward into the morning fog, with another division under Gen. John Gibbon in support. Together, these forces numbered about 8,000 and were sent to attack the 38,000 troops assembled by Stonewall Jackson on top of Prospect Hill in now-fortified positions and supported by roughly 100 cannons. And to reach the base of the hill, the Union troops would have to cross nearly a mile of open farm field. The approach is now known to history as “The Slaughter Pen.”

This farmhouse is probably not the original one that stood here, but it’s consistent with the barren, unfriendly terrain that Meade’s and Gibbons’ forces would have had to march across.

As the Union troops began moving toward Prospect Hill, they were startled by cannon fire coming at them close by from a right angle to their line (known as “enfilading fire”). A 24-year-old Confederate major named John Pelham was serving as J.E.B. Stuart’s Chief of Artillery. He had positioned his two cannons far in advance of the Confederate line and only a quarter mile from the passing Union force. By frequently moving position, Pelham was able to avoid the intense shelling from several Union batteries and continued wreaking havoc on Meade’s division. One of the two pieces was soon destroyed, and eventually the unit ran out of ammunition and retreated to Stuart’s position—but “the gallant Pelham,” as Lee termed him, had delayed the Union attack for almost 2 hours. (Painting of Pelham’s battery by Don Troiani.)

With no one firing rifles or cannons at me, I was able to reach the top of Prospect Hill far faster than any of the Civil War combatants. There were remnants of snow, much like there would have been on Dec. 13, 1862.

Now known as Lee Drive, Gen. Lee’s dirt road along the top of the ridge has since been widened and paved. The road proved to be instrumental to the Confederates.

The earthworks prepared by Stonewall Jackson’s troops at Prospect Hill have eroded substantially since 1862, but they are still plainly visible. The commanding position over the Slaughter Pen must have looked impregnable to the Union troops—but it wasn’t.

In the distance is a stone pyramid, next to the modern tracks of what was the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad. It is known as “Meade’s Pyramid,” but it was actually built through the efforts of the Confederate Memorial Literary Society. Regardless of how it got there, the monument marks the position reached by Gen. Meade’s division of Union troops. When Stonewall Jackson’s generals established their defensive positions at Prospect Hill, they left a sizable gap in the middle. That position could only be approached through a swampy area that was considered impassable. But Meade’s division somehow made it through.

Taking advantage of the gap in the Confederate line, the Federal soldiers split Jackson’s forces in two and attacked them outward in both directions. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting ensued, but the Union commanders’ calls for reinforcements went unanswered by Gen. Franklin. Had Franklin attacked with his full force and taken advantage of this gap, the Union almost certainly would have routed the Confederates here, fulfilling the first half of Burnside’s plan. Without additional support, however, Meade’s forces became overwhelmed and had to retreat as Jackson rushed his troops to the position.

Gen. Gibbon did not order his support division to join Meade’s attack, despite being urged to by subordinate officers. Instead, his men advanced directly toward the Confederate line without the cover of the swamp. Gibbon, a southerner who joined the Union Army, was unknowingly attacking a position manned in part by his own three brothers. His division engaged in fierce combat with the Confederates but were beaten back decisively.

Gen. Burnside repeatedly sent orders for Franklin to move his other forces into the battle, but Franklin did not act on these orders. By the end of Dec. 13, the Union casualties at Prospect Hill (killed, wounded, or captured) were 5,000, while the Confederates lost 4,000. If Franklin had thrown a substantial portion of his other 32,000 soldiers into the attack, the outcome of the battle might well have been far different—and the Civil War might have ended in 1862, rather than dragging on for another 2½ years.

On my way back down from Prospect Hill, I stopped for a quick look at Braehead Manor. It was built in 1858 for John Howison and his wife Anne Richards Lee Howison, a distant cousin of Robert E. Lee. Gen. Lee and Gen. Longstreet ate breakfast at Braehead on the morning of the battle. Braehead was owned by Howison descendants until 2008 and until recently it was used as a bed and breakfast. (We’ll hear more of John Howison’s sister, Jane Howison Beale, in a bit.)

The Battle Continues—Horrifically

While the Federal forces were advancing only a limited attack in the south at Prospect Hill, the second phase of Burnside’s plan was initiated at Fredericksburg. This one would prove far more disastrous for the Union Army than the first, and for much the same reasons: Inept leadership and adverse terrain. As shown in Alfred Waud’s drawing, between the city and the distant Marye’s Heights lay over a half mile of mostly empty fields, with minimal cover available for advancing Federal troops.

Just 200 yards outside of town, moreover, there was a canal ditch, which diverted water from the Rappahannock to the farms and households of Fredericksburg. It was about 15 feet across and 5 feet deep and spanned the entire field between the city and Marye’s Heights. Today, the ditch is still there, but it lies underneath Kenmore Avenue. Farther north, the canal is still in the open, as shown in this photo.

Although there were three wooden bridges over the canal ditch, the Confederates had removed all the planks, leaving only the narrow stringers. A long row of attackers would have to funnel down to a tight column to cross (unsteadily), or clamber down into the ditch, wade across, and then climb back up. Either way, they would represent an easy target for the Confederate artillery on Marye’s Heights. Union scouts were aware of the ditch, but, by some accounts, Gen. Burnside could not see it through his binoculars and refused to believe it existed. (Drawing by J.G. Keyser, showing canal ditch in foreground, courtesy of Brown University.)

In the Union’s favor, there was a modest embankment another 200 yards past the ditch, as shown in the following photo. It offered enough shelter for the officers to organize their men into battle positions. However, once the soldiers advanced over the top, they would again be sitting ducks with yet another 450 yards to go before reaching the Confederates.

A slight rise, or “swale,” sat about 125 yards from their enemy. In a prone position, Union soldiers could stay largely out of view and fire their rifles at Marye’s Heights. The only other meaningful shelter was provided by the nearby Stratton House, which—surprisingly—is still standing. Beyond the swale and the Stratton House, there was simply no cover whatsoever.

The open terrain would not have mattered so much if the Confederates similarly lacked cover—but their circumstances were just the opposite. On the western, defensive side, Gen. Longstreet had positioned about 2,000 riflemen at Telegraph Road (now called the Sunken Road). A 4-foot stone retaining wall provided almost perfect cover for them. Portions of the original stone wall still exist, as shown here, with the remainder having been rebuilt. As indicated in the sketch, the road was also more sunken in those days. The Confederates could stand and shoot, then fall back to reload while others took their place shooting across the open field.

This famous Matthew Brady photograph shows fallen Confederate shooters at the Sunken Road after the battle. Despite the grotesque appearance, there aren’t many bodies in sight. In total, the Confederates had about 1,000 casualties at this northern end of the battle. Most of the killed and wounded were hit by Union fire as they descended from Marye’s Heights to reinforce the Sunken Road position.

Marye’s Heights lay immediately beyond the Sunken Road and represented another huge tactical advantage for the Confederates. The 50 cannons of Longstreet’s batteries were spread out along the ridge, allowing gunners to concentrate their fire at every point across the field. The Heights also provided cover for the 40,000 infantry troops positioned there. Longstreet made his headquarters in the mansion at the top of the ridge. Brompton Manor was built sometime before 1821, and in 1838 it was purchased and extensively modified by John L. Marye. Today, Brompton serves as the home for the President of Mary Washington University.

This photo shows Brompton after the battle. As noted, almost every large building that survived was used as a hospital, and the Confederate soldiers in the photo are recuperating from wounds. Note the trenches dug in the front yard as part of the defenses. Today, Brompton still bears many of the scars of the battle.

Of the several houses that stood along the Sunken Road, only the Innis House remains. This house and the nearby Stephens House were both owned by one Martha Stephens. She was apparently quite a colorful individual. By her own account, Ms. Stephens was in her house throughout the Union attack, aiding injured Confederate soldiers. She would later exclaim how embarrassed she was when Gen. Lee visited the battlefield and found her wearing a dress that didn’t cover her lower legs—a consequence, she said, of ripping up her dress to make bandages for the wounded. Her house survived the battle, despite as many as 1,000 bullet holes, but burned in 1913.

Most of the damage sustained by the Innis House was repaired over the years. The National Park Service acquired the house in 1969 and undertook a thorough renovation. In the process, they discovered numerous bullet holes and shell damage, some of which was found behind layers of wallpaper.

This view from atop Marye’s Heights emphasizes the advantage available to the Confederates. From here, the artillery could easily fire over the troops at the Sunken Road and hit the advancing Union attackers.

Keep in mind, also, that the field beyond the Innis House was virtually barren of trees or other cover in 1862, as illustrated in this dramatic painting. Since that time, entire neighborhoods have sprung up and now cover most of this part of the battlefield. (Although this painting is widely used, I’ve been unable to identify the artist. If you know, please advise, as I’d like to add a citation.)

Despite the massive disadvantage posed by the terrain, Gen. Burnside ordered the Union infantry to attack. Again, his orders were vague, calling on Gen. Sumner to begin with “a division or more.” The attack commenced at about 11:00 a.m., initially with Gen. William French’s division of three brigades—roughly 6,000 men. These soldiers bravely advanced in three waves, by brigade, each in the classical “battle line” formation and knowing full well the odds against them. As Frank O’Reilly of the National Park Service wrote, “Beyond was a landscape whose horror would lodge in the American consciousness. Five hundred yards of open field, broken only by the remnant fences of the town’s fairgrounds and a single house, owned by wheelwright Allen Stratton. This would be the defining landscape of Fredericksburg.”

The Confederate shelling began as the first brigade approached the canal ditch, blowing gaps into the line of Union infantry. The troops reorganized in the lee of the embankment, and by 1:00 p.m. they climbed over and began their quarter-mile march toward Marye’s Heights. Fences from the city’s fairgrounds impeded their progress, and the intensive shelling began again once they were in the open. Gen. Burnside and his officers had seen the Confederate batteries and anticipated significant losses. But they hadn’t recognized the dangers posed by the infantry at the Sunken Road.

Upon reaching the shallow swale, French’s first brigade stopped to rest and reorganize. Shortly after, when they stood to charge the final 125 yards to the Confederates, they were instantly met by a solid sheet of flame as 2,000 rifles discharged in their direction. With reinforcements from Marye’s Heights, there were now several rows of shooters behind the stone wall, with one line firing and immediately being replaced by the next, and so forth. A virtually continuous volley resulted, with catastrophic results for the Union attackers. By the time French’s first brigade fell back to the swale, a fourth of their number were dead or wounded.

As the first brigade huddled at the swale, the second appeared and faced the same apocalypse, this time with 50 to 60 percent casualties. French’s third brigade approached with similar results, leaving the shattered remains of the entire first division lying on the ground, either dead, wounded, or sheltering at the swale.

Later, a New York Times correspondent wrote, “Gen. French’s division went into the fight six thousand strong; late at night he told me he could count but fifteen hundred.”

For 4½ hours, this pattern repeated itself as Generals Burnside and Sumner ordered division after division into the attack. Many were experienced veterans of earlier battles, while some were raw recruits. In all, 30,000 Union soldiers in 17 brigades crossed the “Killing Field” in what proved to be a hopeless effort to rout the Confederates. So much ammunition was expended against the Union forces that the Confederate infantry and artillery troops both ran out—and were promptly replaced by fresh units with new supplies. The carnage never paused, and some of the Confederates even debated whether such a one-sided contest, at some point, ceased to be warfare and instead became murder. Thousands of accounts exist of the wholesale slaughter that occurred here; consider just one of them, if you will, from the National Park Service:

Green recruits in a new regiment gasped when a shell took one man’s head off, showering them with jets of blood. Another shell exploded directly in front of a Massachusetts regiment, knocking down the whole color guard except the sergeant who carried Old Glory; after the blast he still stood, dazed and helpless in the acrid sulfur haze, clasping the flag to his breast with the bleeding stumps of his forearms. The man who took the staff from the handless sergeant was himself killed in a few moments, as was the one who took it from him.

Each new wave of attackers had to run by—and often literally on top of—their fallen comrades from the earlier charges. Some of the wounded grabbed at their pants legs as they crossed, urging them to turn back or face certain death or injury. (Painting “Clear the Way” by Don Troiani.)

Several of Burnside’s senior officers advised a change in tactics, since the current approach was clearly not working. One idea was to make a massed bayonet charge, sufficient to overrun the defenders. Another was to move the troops farther north and attempt to encircle Lee’s left flank. Gen. Joseph Hooker personally crossed the Rappahannock and reconnoitered the battlefield more closely; he returned and advised Burnside against any further charges. Burnside rejected his advice and all the alternatives.

By the time darkness fell and the last Union charge had been repulsed, not a single Union soldier had managed to get within 30 paces of the stone wall. Approximately 8,000 men in blue uniforms lay dead or wounded on the field. Of the Confederate defenders in gray, about 1,000 had been killed, wounded, or captured. Including the casualties from the southern end of the battle, the Union had lost 12,653 men, and the Confederates 5,377. (Painting of “Taps” by Dan Nance.)

Aftermath

As I roamed Marye’s Heights, thinking of the hellish fighting that had taken place, I noticed the brick wall surrounding the Willis Cemetery. I assumed that it would have provided strong cover for the Confederates on top of the Heights, but I was wrong. Shelling by Union artillery at Stafford Heights knocked down most of the walls—and many of the gravestones, leaving only the marble gate standing.

On the evening of December 13, as thousands of wounded Union soldiers lay shivering on the Killing Field, Gen. Burnside conceived a plan to make one final, overwhelming attack on the following morning. He would personally lead this charge, at the head of his old unit, the IX Corps that he had commanded at Antietam and elsewhere. By the next morning, his advisors talked him out of it. There was scattered firing back and forth on December 14, but no other action. Late in the day, Burnside asked Lee for a truce to attend to the wounded and dead. The Union soldiers were buried where they lay. The Confederates continued to entrench their positions, anticipating further attacks by the Federals. Gen. Burnside and his advisors mulled over their options. That night, an Aurora Borealis appeared—a very rare occurrence in Virginia. To many of the southerners, it was Heaven’s symbol of their great victory and an omen of God’s continuing support for their cause. To the northerners, it was Heaven’s display of the Northern Lights to provide solace to the dead and dying. The next day, the Army of the Potomac withdrew from Fredericksburg. Gen. Burnside was relieved of his command 3 weeks later by President Lincoln, and Gen. Hooker was appointed to the position.

The Army of the Potomac returned to the Fredericksburg area in late April 1863, losing the Battle of Chancellorsville, and again a year later, fighting “a ghastly, fiery stalemate” at the Battle of the Wilderness. A week later, the two armies fought “the war’s most intense hand-to-hand and close combat.” Gen. Lee was able to build new defensive earthworks, forcing Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to abandon the battle after 2 weeks of horrific fighting. It was a victory for the Confederates, but Lee’s forces were substantially diminished. The North, in contrast, had a steady supply of new troops and new armament. The fighting continued in Virginia for almost another year, culminating in Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

After the Civil War, the Union dead at Fredericksburg were reburied in the new Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

A minority received stone markers with their names and home states engraved. This is the marker for Joseph Housel, Jr., who was 18 when he enlisted in the 4th New York Heavy Artillery in January 1864. He was killed at the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, as was his cousin. Six months later, Joseph’s older brother Charles died after being wounded at the Second Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia. All three of these young men were from Canandaigua, New York. (Photo of Joseph Housel, Jr. courtesy of Leif HerrGesell’s excellent article, “Common Valor.”)

Unlike Joseph Housel, over four-fifths of the Union dead buried at the Fredericksburg National Cemetery could not be identified and have markers showing only the plot number and the number of men buried in that specific grave. While most of the burials were completed by 1868, additional remains were discovered and reburied for decades.

The National Cemetery is a quiet, contemplative place, perfect for reflecting upon the horrors of war and realization of the cost to the nation. The headstones continue, as far as the eye can see.

Elsewhere in Fredericksburg

Having toured the battlefield, I had enough time remaining to visit other sites in Fredericksburg. This was the residence for the superintendent of the Fredericksburg National Cemetery. The one-story stone portion was built in 1871, with the upper story and mansard roof added about 2 years later.

Unlike most of the grand mansions in and around the city, Smithfield Manor survived the battle largely intact. Gen. Franklin made his headquarters here, and (of course) it subsequently served as a hospital. Today it is the clubhouse for the Fredericksburg Country Club. The original Smithfield mansion was built in 1753 but burned 66 years later. The current building was completed in 1822.

The bridges across the Rappahannock River were rebuilt long ago, including this railroad crossing in 1925.

While photographing the bridge, I couldn’t help noticing the great many seagulls that had collected nearby.

As a young couple approached on the dock, the gulls took flight in every direction. Perhaps having seen Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds once too often, the couple wasted no time in leaving the area!

This old house would be perfect for the modern, “tiny home” trend.

While parked and looking for the embankment described earlier, I couldn’t help noticing the stately manor in the distance. (Incidentally, the top went down as soon as the temperature reached 40 degrees.)

When “Federal Hill” was built (probably in the 1780s), it was considered a country house outside of Fredericksburg. As the city expanded, the mansion became a part of the downtown area. It is believed to have been built by Roger Brooke, who served as Governor of Virginia from 1794 to 1796. It was later owned by Thomas R. Rootes, whose grandson Gen. Thomas R.R. Cobb was killed less than half a mile away during the Battle of Fredericksburg, while commanding the Confederate infantry at the Sunken Road.

Not surprisingly, Fredericksburg has other graveyards in addition to the National Cemetery. This was the original entrance to the Fredericksburg City Cemetery, which opened in 1844. The neighboring William Street was subsequently lowered by several feet, leaving the entrance in its current odd position.

After the battle, the Ladies’ Memorial Association of Fredericksburg arranged for a Confederate Cemetery to be formed adjacent to the City Cemetery. The two separate burial grounds are surrounded by a single brick wall.

Although the Civil War battle was the focus of my trip, it should be noted that there is much more to the history of Fredericksburg. I parked in front of this magnificent old house and went in search of the Washington Monument.

No, not that Washington Monument, this one. It looks somewhat similar but is much smaller than George’s monument in Washington, DC. This one is in honor of his mother, Mary Ball Washington (c. 1708-1789), who is buried here. She had lived in or around Fredericksburg for most of her life.

The monument was constructed in 1894. An earlier one had been partially built in 1833, but it was never completed. The pedestal was finished, but the column lay partially buried next to the base for decades. Adding “injury to insult,” tourists would happily chisel off a piece of stone from the base for a souvenir, leaving the fledgling monument in poor condition. Moreover, during the Civil War battle, the pedestal was heavily damaged by gunfire and shelling. The 1894 memorial has happily survived nicely. According to multiple sources, it was “the first monument ever erected to a woman by women” in the United States.

This unusual rock formation sits just behind the monument. Mrs. Washington was fond of coming to “Oratory Rock” to pray and contemplate life. The formation is now called Meditation Rock. The modest precipice hasn’t changed over time, but it now overlooks a playground.

Did you happen to notice the old brick wall in the background near the monument? Inside lies the “Gordons of Kenmore” family cemetery. Samuel Gordon was one of three brothers who came to the U.S. from Scotland in 1786, and all three flourished in the tobacco trade. (“Kenmore” is an estate built by George Washington’s sister, Betty, and her husband, and later owned by Samuel Gordon.) As shown in the photo, the old graveyard could use a bit of TLC.

Martha Washington lived at Ferry Farm, outside of Fredericksburg, for many years. As she grew older, her children persuaded her to move into the city, and she lived at this home from 1772 until her death 17 years later. She lived to see her son George lead the colonial army to victory over the British and to become the first President of the United States. Her home is now open to the public.

You can’t park anywhere in Fredericksburg without noticing some historic old place. This house was built in 1785, across Lewis Street from Martha Washington’s home. It served as the Betty Washington Inn from 1927 to 1964. I was careful not to park too close, lest some historic old bricks or siding come crashing down on the SL550!

Even more interesting looking was this house across Charles Street from Martha’s home. I later learned that it was the home of Jane Howison Beale and her 9 surviving children. She was born in Fredericksburg in 1815, married a prominent widower when she was 19, and moved with her new husband into the Moncure Conway House in Falmouth (which we saw earlier). In 1846, the couple bought this house, and Jane lived here until her death in 1882.

Jane Beale’s husband died unexpectedly in 1850, leaving her with many debts and the 9 children to care for. She sold their mill in Falmouth, took in boarders, and started a school for girls. She also started a diary, which was not discovered by historians until 90 years after her death. In it, she described antebellum life in the South and, among other topics, the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. Her description of the bombardment of the city is harrowing:

[In the morning,] before we were half dressed the heavy guns of the enemy began to pour their shot and shell upon our ill-fated town, and we hastily gathered our remaining garments, and rushed into our Basement for safety… Our Pastor Mr. Lacy was still with us, and commenced in solemn but tender accents, repeating ‘the 27th Psalm’… As the words “Tho an host should encamp against me, my heart shall not fear” were upon our lips, we startled from our seats by the crashing of glass and splintering of timber close beside us… before I had moved half a doz steps, my youngest Son a boy of ten years, fell against me with the cry, “Oh Ma I’m struck… I soon saw that there was no terrible wound, only a deep redness of the skin about the shoulder and breast… upon going back to the room in which we had been [we] found a twelve lb solid shot near where Sam stood…

About 1 o’clock there was a little cessation of the firing, and we heard my dear brother John’s voice at the door… brother John told us that the town was on fire in many places, a whole row of buildings on Main St were already burnt, and as my house had a shingled roof I thought we would soon be driven from it by fire also. …the heavy Bombardment commenced again and the sound of 173 guns echoed in our ears, the shrieking of those shells, like a host of angry fiends rushing through the air, the crashing of the balls through the roof and upper stories of the house, I shall never forget to the day of my death, the agony and terror of the next four hours, is burnt in on my memory as with hot iron, I could not pray, but only cry for mercy.

Jane Beale was not the only diarist in Fredericksburg at that time. Sixteen-year-old Lizzie Alsop, shown here at right with her sisters Emily and Nannie, was also prolific. In addition to her thoughts on religion, romance, and society, she wrote of the Union occupiers of Fredericksburg: “We Confederates are, generally speaking, the most cheerful people imaginable, and treat the Yankees with silent contempt. They little know the hatred in our hearts towards them—the GREAT scorn we entertain for Yankees. I never hear or see a Federal riding down the street that I don’t wish his neck may be broken before he crosses the bridge.”

Jane Beale was equally contemptuous of the Union occupiers. The families of both diarists owned slaves and bitterly resented the Union invasion of their city and state. Jane Beale expressed a commonly held view that African Americans “were ordained of high Heaven to serve the white man and it is only in that capacity they can be happy useful and respected.” She describes how her “servants” worked hard to care for her and her children during the bombardment and later prevented the looting and destruction of the family’s house—but she did not seem to recognize their valor, intelligence, or dedication in so doing.

Elsewhere in Fredericksburg, I found “Smithsonia,” which was built in 1838 to be the Female Orphan Asylum, housing and teaching up to 15 girls at a time. It has also been a boys’ college dormitory, a private home, a derelict building, and—of course—a hospital during the Civil War.

The original market square dates back to 1728, while the town hall/market house in the background was built in 1814-1816. It is Virginia’s only surviving town hall/marketplace built prior to the Civil War. The building continued to serve as the town hall until 1982, and today it houses the Fredericksburg Area Museum.

I’m not sure when these homes were constructed, but I had to admire their stately entrances.

As the day wore on, the sky became greyer and darker; it was a good time to put the top back up. I’ve parked here on Sophia Street, which used to be Water Street, and which was blasted to bits during the bombardment. It is my imagination, or is the Mercedes frowning haughtily at the ungainly earthmoving equipment in the background?

Farther up Sophia Street, the house on the banks of the Rappahannock could be mistaken for a pre-Civil War dwelling—but it’s not. Before the battle, a number of small, basic houses were situated at this section of the town. All of them were destroyed in the battle.

A Reminder of What They Were Fighting About

As the clouds became lower and darker, they reinforced my sorrowful thoughts about the horrors of the Fredericksburg battle and the Civil War in general.

I had one more stop to make before heading home. I was hoping to get a look at the ruins of another of Fredericksburg’s antebellum mansions, namely “Sherwood Forest.” On my way to cross back over the Rappahannock, I spotted this old stone warehouse. It was built in 1813, on top of the foundations of a 1754 predecessor. Before its closing, visitors loved to dig through the dirt floor in the first level, looking for arrowheads, bullets, and other artifacts (with the owner’s blessing). This view from Sophia Street shows what is actually the third story of the building. All three levels are visible from the river side.

The historic Sherwood Forest mansion is centered in what will become a mammoth housing development. It has been vacant and deteriorating for many years, and I was hoping to get a look at it before it might be bulldozed or just collapse on its own. (2013 photo courtesy of the National Park Service.)

I knew that the main entrance to the former plantation was blocked by a gate, but satellite photos suggested there was a back way in. After smugly driving past the gated entrance, I located and turned onto the bumpy dirt road leading to the back way—and found another sturdy, closed gate, with no fewer than seven “no trespassing” signs. Well, I got the message.

Far away, on top of the hill, Sherwood Forest is still standing, I believe. The best I could do was get a picture of this deteriorating old barn. With luck, the developers will stabilize and preserve the mansion. The barn and other buildings, however, are surely doomed.

Our friendly historian, John Hennessy, has written of the account given by a former enslaved African American at Sherwood Forest of the horrific treatment here of an elderly slave woman, by her ostensibly kind master, Henry Fitzhugh. In response to her efforts to protect her daughter from the master’s amorous desires, the older woman was stripped naked, tied to a tree, severely whipped, washed with a mixture of pepper, salt, and water, then whipped again, and made to dance, all of this in front of the plantation’s onlooking population, black and white.

War was certainly hell and still is, as evidenced by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But there can be no doubt that slavery was every bit as hellish. It took almost 5 years of hellish war to end slavery in the United States, and many more years since to help deliver the promises implicit in the Declaration of Independence. Awareness of this history remains central to the continuing efforts to completely fulfill those promises.

With thoughts of war, injustice, progress, and unfinished business, it was time to retrace my steps back to Maryland. I am indebted to the city of Fredericksburg and the National Park Service for a fascinating and illuminating look into the past.

Rick F.

PS: Unless noted otherwise, historical photographs and drawings are courtesy of the Library of Congress or the National Park Service.

HI Rick as always great writing and quite the history lesson. Sadly it seems we never learn from the past. Thank you for taking the time to share your travels.

Hi Shannon,

Thanks, I’m glad you enjoyed the report! This trip was a real eye-opener, even though I’ve been very familiar with the Antietam and Gettysburg battles for a long time. Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg always struck me as an incredibly poor decision by Robert E. Lee, but I hadn’t been aware of the equally senseless charges ordered at Fredericksburg by Ambrose Burnside.

Interestingly, as Pickett’s forces were charging across the open field at Gettysburg, the Union defenders were shouting, “Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!” as a rallying cry to avenge their massive losses at the earlier battle.

Rick

Rick dear friend, this article with pictures and drawings was beautifully written -also incredibly informative – am reading just days after the shooting in Buffalo – almost impossible to believe we are still where we we are in terms of racial equality – that final story about the elderly slave mother was simply appalling.

Thank you so much!

Hi Vicky!

Thanks much—I’m glad you liked the trip report. I agree 100% regarding racial equality. We’ve come so far compared to where things stood when we were growing up, but there still seems like a long way to go.

Hope to see you in June!

Rick

Excellent pictures and even better writing. In 2011 and 2012, my wife Joann and I went on two 5-day 4-night trips studying Civil War battles. The northern trip covered Antietam and Gettysburg, but the southern trip the following year mirrored your recent trip report. My memory isn’t what it used to be, but your report helped remind me of the trip ten years ago. Thanks for your report. I plan to forward it to a few friends with your permission.

Hi Ben,

Great, thank you! By all means, feel free to forward the report to any and all. (Maybe warn them that it’s 9,000 words!)

I spent all day just in Fredericksburg, but I’ll be back before long to visit the sites of the Chancellorsville and Wilderness battles. Including the cemetery where Stonewall Jackson’s arm is buried…

Rick

Rick I’m saddened again at the horrors of war, and abuse of so many fine human souls.

I read a lot about the Civil War as a very young child, while living in Maryland and then Virginia. I saw daguerreotypes of the horrible scenes. I saw a little of the horrors of war and thought of the photographers who were such heroes to develop those plates on the edge of the battlefield

I had no idea how massive the armies were, and how many casualties. I stood on battlefields with my family, and admired the green beauty I saw there. The sketches and photos say otherwise.

Thank you for this tale and so many more. Thanks for taking the Merc to prepare for your writing. And thanks specially for your fine words and photos. Hat’s off to you sir.

If you go on rougher roads you may need all terrain tires for that Merc, and a lifted suspension.

DaveL

Thank you again for these great pictures. Another great grandfather, Adam Ritter lived at Falmouth when he signed up at Camp Germania as a wagoneer in the Rev. War. After the war, he moved to Winchester purchasing Lot #13 in the old Isaac Hollingsworth area near Shawnee Springs. Camp Germania was mentioned in Adam Ritter’s Rev. records, however I have never been able to pin point exactly where this Rev. War. recruiting camp was set up. It must have been around Fredericksburg-Falmouth area. Thanks again, Rick. I so enjoyed it.

Hi Charlotte,

Wow, you have all sorts of historic ancestors! I looked for information on Camp Germania, but the best I could find was a reference to “Camp Germania Mills” in Virginia, which was cited in the context of the Civil War. No data on its location, unfortunately. I’m sure someone knows about the recruiting center and where it was located, but so far those facts seem to have eluded the Internet.

My most famous relative was Silas Deane, who worked with Benjamin Franklin and others during the American Revolution to procure supplies from France for the Colonial Army. I’m not a direct descendant—just a distant cousin. You can read about him in my trip report, “Heroes, Villains, and Cottages by the Sea: New England by BMW.”

Rick

There is a Dean family in Frederick County and around Elkton, Rockingham County, Virginia. Most likely not your family, but thought you would like to know that a John Dean, Sr. born ca 1762 married Mary KNEISLEY/KNISELY who was born in Shenandoah County (Old Frederick County). They were married in 1787 in Rockingham County. Back to Fort Valley, originally known as Powell’s Big Fort, George KNISELY purchased John Michael Ritter’s property that I mentioned was located with lines on Passage Creek and Miller’s Run at Veach’s Gap in Fort Valley. Thanks again for all the wonderful photos. Enjoy my travels with you.

Magnificent article with magnificent photos! You’ve made my recent trip to Fredericksburg much more meaningful. Nice wheels, too.

Hi Sara,

Thanks much, I’m glad you enjoyed the report, and I trust you found Fredericksburg and its history as fascinating as I did.. The consequences of the poor tactical decisions at that battle are almost impossible to comprehend.

As for the wheels, yeah, it’s a great way to tour!

Rick